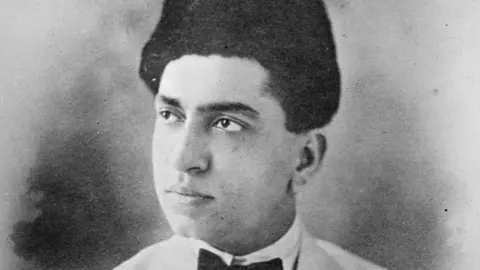

Alami

AlamiIt looked like a simple murder.

One hundred years ago on this day – January 12, 1925. – a group of men attacked a couple on a car ride in an upscale suburb of Bombay (now Mumbai) in colonial India, shooting the man and slashing the woman's face.

But the story that unfolded drew worldwide attention to the case, while its complexity unsettled British rulers at the time and eventually forced an Indian king to abdicate.

Newspapers and magazines described the murder as “perhaps the most sensational crime committed in British India” and it became “the talk of the town” during the investigation and subsequent trial.

The victim, 25-year-old Abdul Qadir Baula, was an influential textile businessman and the city's youngest municipal official. His companion, 22-year-old Mumtaz Begum, was a courtesan on the run from the harem of a princely state and had been living with Baula for the past few months.

On the evening of the murder, Baula and Mumtaz Begum were in the car with three others, who were driving to Malabar Hill, an affluent area on the coast of the Arabian Sea. Cars were rare in India at that time and only the rich owned them.

Suddenly another car caught up with them. Before they could react, he collided with theirs, forcing them to stop, according to intelligence and newspaper reports.

The assailants hurled abuse at Baula and shouted “bring the lady out,” Mumtaz Begum later told the Bombay High Court.

They then shot Baula, who died a few hours later.

A group of British soldiers who inadvertently blundered in on their way back from a game of golf hear the shots and rush to the scene.

They managed to capture one of the criminals, but one police officer received gunshot wounds when an assailant opened fire on them.

Alami

AlamiBefore fleeing, the remaining attackers made two attempts to wrest the injured Mumtaz Begum away from the British officers who were trying to rush her to the hospital.

Newspapers suggested that the assailants' aim was probably to kidnap Mumtaz Begum, as Baula – whom she had met during a concert in Mumbai a few months earlier and had been living with since then – had earlier received several threats to kill her. sheltered

India's illustrated weekly promised readers exclusive pictures of Mumtaz Begum, while police planned to issue a daily press bulletin, Marathi newspaper Navakal reported.

Even Bollywood found the case compelling enough to adapt it into a silent murder thriller within months.

“The case went beyond the usual murder mystery as it involved a rich and young tycoon, a neglected king and a beautiful woman,” says Dhaval Kulkarni, author of The Bawla Murder Case: Love, Lust and Crime in Colonial India.

The fingerprints of the attackers, as media speculated, led investigators to the powerful princely state of Indore, which was a British ally. Mumtaz Begum, a Muslim, lived in the harem of the Hindu king, Maharaja Tukoji Rao Holkar III.

Mumtaz Begum was known for her beauty. “It is said that in her own class, Mumtaz has no equal,” writes K. L. Gauba in his 1945 book “Famous Trials of Love and Murder.”

But the maharaja's (king) attempts to control her — preventing her from seeing her family alone and keeping her under constant surveillance — strained their relationship, Kulkarni says.

“They kept me under surveillance. They allowed me to see visitors and my relatives, but I was always accompanied by someone,” Mumtaz Begum testified in court.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Indore she gave birth to a baby girl who died soon after.

“After my child was born, I did not want to stay in Indore. I didn't want to because the sisters killed the female child that was born,” Mumtaz Begum told the court.

After months, she fled to the northern Indian city of Amritsar, her mother's birthplace, but trouble ensued.

She was also observed there. Mumtaz Begum's stepfather told the court that the Maharaja was crying and begging her to come back. But she refused and moved to Bombay, where the surveillance continued.

The trial confirmed what the media had speculated after the murder: representatives of the maharaja had indeed threatened Baul with dire consequences if he continued to harbor Mumtaz Begum, but he ignored the warnings.

Acting on the directions of Shafi Ahmed, the only assailant caught at the scene, the Bombay police arrested seven men from Indore.

The investigation revealed connections to the Maharajah that were hard to ignore. Most of the men arrested were employed by the princely state of Indore, applied for leave around the same time and were in Bombay at the time of the crime.

The assassination put the British government in a difficult situation. Although it took place in Bombay, the investigation clearly showed that the plot was planned in Indore, which had strong ties with the British.

Calling it “a most embarrassing affair” for the British government, The New Statesman wrote that if it had been a small country “there would have been no particular cause for alarm”.

“But Indore is a powerful feudal bearer of the Raja,” it said.

The British government initially tried to publicly hush up the murder's connection to Indore. But privately he discussed the matter with great anxiety, the communication between the Governments of Bombay and British India shows.

Bombay Police Commissioner Patrick Kelly told the British government that all evidence “at present points to a plot hatched at Indore or at the instigation of Indore to abduct Mumtaz (sic) by hired desperadoes”.

The government was under pressure from various quarters. The Baula community of wealthy Memons, a Muslim community with roots in modern-day Gujarat, raised the issue with the government. His fellow municipal officials mourned his death, saying “there must surely be more behind the scenes”.

Indian lawmakers demanded answers in the upper house of British India's legislature, and the case was even debated in Britain's House of Commons.

Alami

AlamiRohidas Narayan Dusar, a former police officer, wrote in his book about the killing that investigators were pressured to go slow, but then-Police Commissioner Kelly threatened to resign.

The case attracted top lawyers from both the defense and the prosecution when it reached the Bombay High Court.

One of them was Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who would later become the founding father of Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947. Jinnah defended Anandrao Gangaram Phance, one of the accused and a senior general in the Indore army. Gina manages to save her client from a death sentence.

The court sentenced three men to death and three to life imprisonment, but did not hold the Maharaja accountable.

Judge LC Crump, who presided over the trial, noted, however, that “there are individuals behind them (the attackers) that we cannot pinpoint”.

“But when an attempt was made to abduct a woman who had been for 10 years the mistress of the Maharaja of Indore, it is not unreasonable to look upon Indore as the neighborhood from which this attack may have originated,” the judge observed.

The notoriety of the case meant that the British government had to act quickly against the Maharajah. They gave him a choice: face a commission of inquiry or abdicate, according to documents presented to India's parliament.

The Maharaja chose to withdraw.

“I abdicate my throne in favor of my son on the condition that no further inquiry be made into my alleged connection with the Malabar Hill Tragedy,” he wrote to the British government.

After abdicating, the Maharaja caused more controversy by insisting on marrying an American woman against the will of his family and community. She eventually converted to Hinduism and they married, according to a British Home Office report.

Meanwhile, Mumtaz Begum received offers from Hollywood and later moved to the US to try her luck there. She then disappeared into obscurity.