Swastika pal

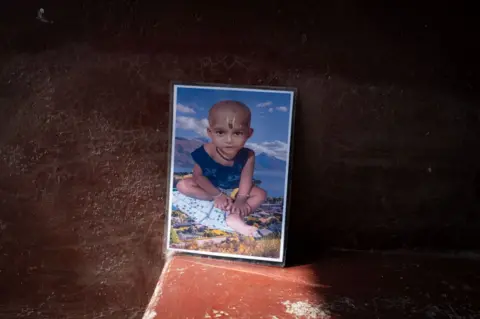

Swastika palMangala Praudhan will never forget the morning when he lost her one -year -old son.

It was 16 years ago, in the ruthless Sundarbans – a huge, raw delta of 100 islands in the Indian state of Western Bengal. Her son Ajit, who had just passed, was full of life: stormy, restless and curious about the world.

This morning, like many others, the family was employed with their daily duties. The brazier had fed Ajit with breakfast and had taken him to the kitchen while cooking. Her husband was out and bought vegetables and her sick mother -in -law rested in another room.

But the little Ajit, always eager to explore, escaped unnoticed. The brazier called to her mother -in -law to watch him, but there was no answer. Minutes later, when he realized how quiet it had happened, panic had come.

“Where is my boy? Has anyone seen my boy?” She shouted. The neighbors came to the rescue.

Despair quickly turned into a broken heart when her son -in -law found Ajit's tiny body to swim in the lake in The courtyard in front of their Pajan House. The little boy had deviated and slid into the water – a moment of innocence became an unthinkable tragedy.

Swastika pal

Swastika palMangala today is one of the 16 mothers in the area walking on foot or by wheel up to two improvised nurseries created by a non-profit organization where they care, feed and train about 40 children who are left by their parents on the way for work. “These mothers are the rescuers of children who are not theirs,” says Sujo Roy of the Institute for Children in Need (Cini), who created nurseries.

The need for such care is urgent: countless children continue to be drowning in this river area, which is littered with lakes and rivers. In every home there is a pond used for bathing, washing and even drawing drinking water.

A 2020 study at the Organization for Medical Research The George Institute and Cini found that nearly three children between the ages of one and nine years were drowning daily in the Sundarbance region. The peak of drowns was in July, when the monsoon rains began, and between ten in the morning and two o'clock in the afternoon. Most children were unattended at the time as the caregivers were busy with housework. About 65% drowned within 50 meters of home, and only 6% received care from licensed doctors. Healthcare was in chaos: the hospitals were scarce and many public health clinics were dysfunctional.

Swastika pal

Swastika palIn response, the peasants adhered to ancient superstitions to save saved children. They turned the child's body over an adult's head, singing calls. They hit the water with sticks to banish the spirits.

“As a mother, I know the pain of losing a child,” Mangal told me. “I don't want any other mother to endure what I did. I want to protect these children from drowning. We live in so many dangers anyway.”

Life in Sundarbans, the home of four million people, is a daily struggle.

The tigers known to attack people are wandering dangerously near and entering crowded villages where the poor earn Living, often squatted on land.

People catch fish, collect honey and collect crabs under the constant threat of tigers and poisonous snakes. From July to October, rivers and lakes swell due to torrential rains, cyclones overwhelm the region and lush waters absorb villages. Climate change worsens this uncertainty. Nearly 16% of the population here is one to nine years old.

Swastika pal

Swastika pal“We have always cohabited with water without knowing the dangers until a tragedy happens,” says Suja Das.

The Sudzha's life turned three months ago when her 18-month-old daughter Ambika drowned in the lake in their common family home in the curls.

Her sons were in coaching courses, some family members had gone to the market, and an elderly aunt was busy working at home. Her husband, who usually works in the southern state of Kerala, was home that day and was repairing a fishing net on a nearby trawler. The Suja had gone to bring water from a local manual pump, as the promised water connection at her residence had not yet been made.

“Then we found her swimming in the lake. Rain raining, the water had increased. We took her to a local charlatan who declared her dead. This tragedy awakened us what we need to do to prevent such tragedies in the future, “Sudzha says.

Swastika pal

Swastika palSudzha, like others in the village, plans to enclose her pond with bamboo and nets to prevent children from wandering in the water. She hopes children who do not know how to swim, will be trained in rural reservoirs. She wants to encourage neighbors to learn CPR to provide life -saving help to saved children.

“Children do not vote, so there is often no political will to deal with these problems,” says Mr. Roy. “That is why we focus on building local stability and the spread of knowledge.”

In the last two years, about 2000 residents of the village have completed training for cardiac resuscitation. Last July, a peasant rescued a drowning child, reviving him before being sent to the hospital. “The real challenge is in the creation of nurseries and the increase in awareness of the community,” he adds.

Applying even simple solutions is a challenge due to costs and local beliefs.

Swastika pal

Swastika pal Swastika pal

Swastika palIn the sundarbans, superstition for angry aquatic deities made it difficult for people to surround their lakes. In a neighboring Bangladesh, where drowning is the leading cause of the death of children aged one to four years, wooden baskets were introduced into the yards to protect the children. However, the correspondence was low – the children did not like them and the villagers often used them for goats and ducks. “This has created a false sense of security and the drowning levels have increased slightly in three years,” says Dzhangur Dzhangur, an epidemiologist on injury at the George Institute.

In the end, non -profit organizations created 2500 nurseries in Bangladesh, reducing deaths by drowning by 88%. In 2024, the government expanded this to 8,000 centers, which favored 200,000 children a year. Water -rich Vietnam focuses on children between the ages of six and 10, using deaths for decades to develop policies and learn survival skills. This reduced the drowning rate, especially among students traveling on waterways.

Swastika pal

Swastika pal Swastika pal

Swastika palDrown remains a major global problem. In 2021, approximately 300,000 people drowned – over 30 lives lost every hour, according to the WHO. Nearly half were under 29 years of age and one quarter were under five years old. India's data are scarce, officially registered about 38,000 deaths since the drowning in 2022, although the actual number is probably much higher.

In the sundarbans, raw reality is always present. For years, the children have been left to walk freely or have been tied with ropes and fabric so that they do not wander. The rattling ankles were used to warn parents about their children's movements, but in this ruthless, water -surrounded landscape, nothing really feels safe.

Kacoli Das' six -year -old son entered the Lake's over -summer Lake as he was supplying a piece of paper to a neighbor. Unable to distinguish between road and water, Ishan drowned. He has received seizures as a child and cannot learn to swim because of the risk of fever.

“Please ask every mother: Circle your lakes, learn how to revive children and teach them how to swim. It's about saving lives. We can't afford to wait, “says Kacoli.

For now, nurseries serve as a lighthouse of hope, offering a way to protect children from the dangers of water. Recently, the four -year -old manic Pal sang a cheerful song to remind her friends: I will not go alone to the lake/unless my parents are with me/I will learn to swim and stay on the surface/and live my life without fear.