The BBC

The BBCA Ukrainian official told the BBC they hoped a New Year's prisoner swap with Russia would happen “anyday”, although arrangements could fall through at the last minute.

Petro Yatsenko of Ukraine's Prisoner of War Treatment Headquarters said negotiations with Moscow over prisoner swaps had become more difficult in recent months since Russian forces began making significant advances on the front lines.

There were only 10 exchanges in 2024the lowest number since the full-scale invasion began. Ukraine has not released the number of prisoners of war held by Russia, but the total is believed to be more than 8,000.

Russia has made significant gains on the battlefield this year, raising fears that the number of Ukrainians being captured is rising.

One of those repatriated in the last exchange in September 2024. is Ukrainian Marine Andrii Turas. In an apartment in the Ukrainian city of Lviv, Andriy and his wife Lena tell me the remarkable story of their ordeal. Both were captured during the defense of the city of Mariupol in 2022.

“They were lecturing us about how Ukraine never existed,” Lena, a combat medic, says of her Russian captors. “They tried to erase our Ukrainian identity in our heads.

Lena was released after two weeks of captivity. But the psychological scars of what she experienced in a Russian POW prison remain. “We kept hearing screams, we knew the men (in our section) were being tortured,” she says.

They beat us mercilessly, with fists, with sticks, with hammers, with whatever they could find”, says Andrii. “They stripped us naked in the cold and forced us to crawl on the asphalt. Our legs were torn apart and we were left terrified and frozen.'

“The food was appalling – sauerkraut and rotten fish heads. It's just a nightmare,” says the Marine. “It's like waking up from a bad dream in the middle of the night, drenched in sweat, terrified.”

Andrii's arrest lasted much longer than that of his wife – two and a half years.

On his release from the prisoner exchange three months ago, Andrii met his two-year-old son Leon for the first time. When the couple was captured by Russian forces, Lena didn't know she was expecting.

“When I found out I was pregnant I just cried, first from happiness but then from sadness because I couldn't tell my husband.

“I kept writing him letters, telling him that he was finally going to have the child he had wanted for so long,” says Lena, her eyes shining. “But he didn't get a single letter.”

I ask Andrii how it feels to meet his son for the first time. “I thought I was the luckiest man in the world,” he says, grinning.

Although the BBC cannot independently verify everything that Lena and Andriy have told us, their accounts have been corroborated by international organizations that have interviewed hundreds of Ukrainian POWs.

The UN says Russia subjects Ukrainian prisoners to “widespread and systematic torture and ill-treatment … including severe beatings, electric shocks, sexual assault, suffocation, prolonged stress positions, forced excessive exercise, sleep deprivation, mock executions, threats of violence and humiliation . “

In a statement to the BBC, the Russian embassy in London said: “The claims you have described are patently false. Captured Ukrainian fighters are treated humanely and in full compliance with the provisions of the relevant Russian legislation and the Geneva Convention. They are provided with good quality food, shelter, medical assistance, religious and intellectual sustenance.”

Andrii is undergoing rehabilitation at a medical facility in Lviv. But he still has time to enjoy the holidays with his wife and son. It's the Turas family's first Christmas together, and the best gift for little Leon is having daddy home.

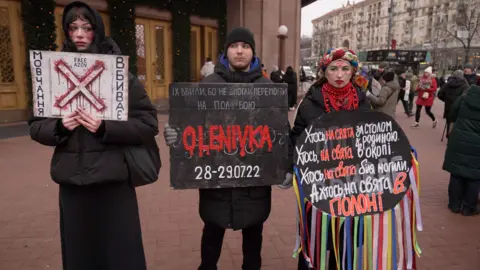

But many Ukrainians are still desperately waiting for news about their loved ones. In the center of Kyiv, relatives and activists gather for a special Christmas demonstration to call for the release of Ukrainian prisoners.

They stand for hours in the bitter cold, lining one of the capital's main streets, as passing drivers honk their horns in a deafening cacophony of solidarity.

“We're hoping for a Christmas miracle,” says Tetyana, whose 24-year-old son Artem was captured almost three years ago. “My son's release is my deepest wish. I imagined our meeting 100 times, when he and I hug each other, and his eyes light up and he is finally on home soil.”

29-year-old Lilia Ivashchik, a ballet dancer at the Kyiv National Operetta Theater, is also at the protest with a red placard. Russian forces captured her boyfriend Bogdan in 2022. She has had no contact with him since.

“I can say that it's hard for me to be alone, but I don't want to say it because I keep thinking about how he's doing there,” says Lilia.

Backstage at the theater, Lilia shows us the messages she still sends to Bogdan almost every day – pictures of little hearts. “I miss him a lot. He needs to be saved and get his freedom back,” she says, her lower lip quivering. Messages are unread.

Lilia invites us to watch her in a special Christmas performance. Dance is a holiday favorite in Ukraine: Johann Strauss' Blue Danube Waltz, written in 1866 to lift the spirits of post-war Austrian audiences. The theater is packed.

“Christmas is a painful time,” she says as she prepares to go on stage. “There's really no festive mood.”

With the end of the performance, the theatergoers rush to put away their coats. After almost three years of war, almost everyone here has a loved one fighting on the front lines, captured or killed in action.

“Many people in Ukraine are facing difficult situations,” says Lilia. “We are just waiting for the time when we can celebrate together again. We must remember to thank our military for having holidays at all.