Yves Blouin

Yves Blouin“I know you can die twice. First comes physical death… to be forgotten is a second death,” notes screenwriter Yves Blouin in an epilogue at the end of his mother's autobiography.

Eve understands that feeling more than most.

In the 1950s and 1960s, her mother, the late André Blouin, threw herself into the fight for a free Africa, mobilizing the women of the Democratic Republic of the Congo against colonialism and rising to become a key adviser to Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the DR Congo and a revered hero of independence.

She exchanged ideas with famous revolutionaries such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Sekou Toure of Guinea and Ahmed Ben Bela of Algeria, but her story is almost unknown.

In an attempt to redress this injustice, Blouen's memoir, My Country, Africa: Autobiography of a Black Passionist, is being republished after being out of print for decades.

In the book, Blouin explains that her longing for decolonization was sparked by a personal tragedy.

She grew up between the Central African Republic (CAR) and Congo-Brazzaville, which at the time were French colonies called Ubangi-Shari and French Congo respectively.

In the 1940s, her two-year-old son René was treated in a hospital for malaria in the CAR.

Renee was of mixed race like his mother, and because he was one-quarter African, he was denied medicine. Weeks later, Rene was dead.

“My son's death politicized me as nothing else could,” Blouin wrote in his memoirs.

She added that colonialism was “no longer a matter of my own ill-fated fate, but a system of evil whose tentacles reach into every phase of African life.”

Blouin was born in 1921. in the family of a 40-year-old white French father and a 14-year-old black mother from the CAR.

The two met when Blouin's father passed through her mother's village to sell goods.

“Even today, the story of my father and mother, although it causes me a lot of pain, still amazes me,” Blouen said.

When she was only three, Blouin's father placed her in a mixed-race convent girls, which was run by French nuns in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville.

That was it common practice in the African colonies of France and Belgium – it is believed that thousands of children born to colonialists and African women were sent to orphanages and separated from the rest of society.

Blouen writes: “The orphanage serves as something of a garbage can for the dregs of this black and white society: the mixed-blood children who don't fit in anywhere.”

Yves Blouin

Yves BlouinBlouin's experience at the orphanage was extremely negative – she wrote that the children in the institution were whipped, malnourished and verbally abused.

But she was wayward—she ran away from the orphanage at 15 after the nuns tried to force her into marriage.

Blouin ended up marrying twice of his own free will. After René's death, she moved with her second husband to Guinea, a West African country that was also ruled by the French.

At the time, Guinea was in the midst of a “political storm,” she wrote. France had promised the country independence, but also required Guineans to vote in a referendum on whether or not the country should maintain economic, diplomatic and military ties with France.

The Guinean branch of the pan-African movement Dessemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA) wanted the country to vote no, arguing that the country needed full liberation. In 1958 Blouen joined the campaign, driving across the country to speak at rallies.

A year later, Guinea secured its independence by voting “No” and Sékou Touré, the leader of Guinea's RDA, became the nation's first president.

By this time, Blouin had begun to gain considerable influence in postcolonial, pan-Africanist circles. She wrote that after Guinea became independent, she used this influence to advise the new CAR President Barthélemy Boganda, persuading him to step down in a diplomatic row with Congolese-Brazzaville's post-independence leader Fulber Yulu.

But consulting was not all Blouen had to offer this rapidly changing Africa.

At a restaurant in Guinea's capital, Conakry, she met a group of liberation activists from what would later become DR Congo. They called on her to help them mobilize Congolese women in the struggle against Belgian colonial rule.

Blouin was pulled in two directions. For one thing, she had three young children – including Eve – to raise. On the other hand, “she had the restlessness of an idealist with a certain anger at the world as it was,” Eve, now 67, told the BBC.

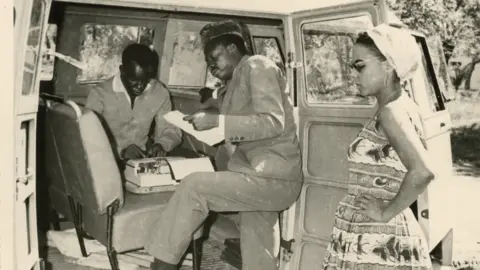

In 1960, with Nkrumah's encouragement, Andre Blouin flew alone to the DR Congo. She joined prominent male liberation activists such as Pierre Mulele and Antoine Gizenga along the way, campaigning throughout the country's 2.4 million square kilometers (906,000 sq mi). She cut a striking figure as she traveled through the bush with her tresses, form-fitting dresses and chic translucent shades.

Yves Blouin

Yves BlouinIn Kahemba, near the Angolan border, Blouin and her team paused their campaign to help build a base for Angolan independence fighters fleeing Portuguese colonial rule.

She addressed crowds of women, encouraging them to demand gender equality as well as Congolese independence. She also had a knack for organization and strategy.

Soon colonial powers and the international press picked up on Blouin's work. They accused her of being, among many things, Nkrumah's mistress, Sekou Toure's agent and “a courtesan to all African heads of state”.

She attracted even more attention when she met Lumumba.

In his book, Blouin described him as a “flexible and elegant” man whose “name is written in golden letters in the sky of the Congo”.

When the country gained its independence in 1960, Lumumba became its first prime minister. He was only 34 years old.

Lumumba chose Blouin as his “chief of protocol” and speechwriter. The pair worked so closely that the press called them “Lumum-Blouin”.

Blouin was described by the US magazine Time as “a beautiful 41-year-old woman” whose “steel will and quick energy make her an invaluable political aide”.

But a series of disasters befell the Lumum-Blouen team – and the newly formed government – just days into their reign.

First, the army mutinied against the white Belgian commanders, sparking violence across the nation. Belgium, the United Kingdom and the United States then supported the secession of Katanga, a mineral-rich region in which all three Western nations had interests. Belgian paratroopers swooped back into the country, ostensibly to restore security.

Blouin described the events as a “war of nerves”, with traitors “organizing everywhere”.

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissShe wrote that Lumumba was “a true hero of modern times”, but also admitted that she found him naive and at times too soft.

“It is true that the most conscientious are often the most grievously deceived,” she said.

Within seven months of Lumumba taking over, Army Chief of Staff Joseph Mobutu took power.

On January 17, Lumumba was shot dead with the tacit support of Belgium. It is possible that the UK is complicitwhile the US had organized previous plots to kill Lumumba – fearing that he had sympathized with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

In her book, Blouin says the shock and grief caused by Lumumba's death left her speechless.

“I've never run out of things to say before,” she wrote.

She was living in Paris at the time of the assassination, having been forced into exile following Mobutu's coup.

To ensure that Blouin would not speak to the international press, the authorities had her family – who had moved to Congo – remain in the country as “hostages”.

The split was devastating for Blouen, who, as Eve describes, was “very protective” and “very motherly”.

Reflecting on her mother's personality, Eve adds: “I wouldn't want to go against her because even though she had a big and generous heart, she could be quite fickle.”

While Blouin was in exile, soldiers ransacked her family home and brutally beat her mother with a gun, permanently damaging her spine.

Blouin's family was finally able to join her after months of separation.

They spent a short period of time in Algeria – where they were offered asylum by the country's first post-independence president, Ahmed Ben Bella.

Then they settled in Paris. Blouin remained involved in Pan-Africanism from afar “in the form of articles and almost daily meetings,” Yves writes in the memoir's epilogue.

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissWhen Blouin began writing her autobiography in the 1970s, she still held great reverence for the independence movements to which she had devoted herself.

She praised Sekou Toure, who by this point had established a one-party state and ruthlessly suppressed freedom of expression.

Blouin, however, fell into deep despair that Africa had not become “free” as she had hoped.

“It is not outsiders who have done the most damage to Africa, but the crippled will of the people and the selfishness of some of our own leaders,” she wrote.

She mourned the death of her dream so much that she refused to take medication for the cancer that was ravaging her body.

“It was horrible to watch. I was absolutely powerless,” said Eve.

Blouin died in Paris on April 9, 1986. at the age of 65. According to Eve, her mother's death was greeted by the world with “grim indifference”.

However, she remains an inspiration in some corners. In the DR Congo's capital, Kinshasa, a cultural center named after Blouin offers the likes of educational programs, conferences and film screenings – all underpinned by a pan-African spirit.

And through My Country, Africa, Blouen's extraordinary story is coming out a second time, this time in a world that is taking a greater interest in the historical contributions of women.

New readers will learn about the girl who went from being forced by the colonial system to fighting for the freedom of millions of black Africans.

My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Passionaria, published by Verso Books, goes on sale January 7 in the UK

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC