Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCOn the night of December 6, Mohammed al-Nadaf, a soldier in the Syrian army, was at his position in Homs.

As rebels led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) swept into the city, days after seizing control of Aleppo and Hama in a lightning offensive, Mohammed decided he did not want to fight.

“We had no orders, no information. I took off my uniform, left my weapons and walked towards my village in Tartus,” he said.

Around the same time, Muhammad Ramadan was in a position on the outskirts of the capital, Damascus.

“There was no one to command us. Many of our commanders fled before us. So I thought why should I die and fight for someone who didn't even give me enough salary to feed my family?

“For our daily rations as soldiers we only got one egg and one potato.”

The next morning he also left his position and went home.

The soldiers' testimonies provide insight into the rapid collapse of the regime of ousted President Bashar al-Assad.

To many of his demoralized and poorly paid ground forces, the speed with which their defenses crumbled in the face of the rebel offensive came as no surprise.

Many soldiers told us they were paid less than $35 (£28) a month and had to do other work to get by in a country where it would only cover a fraction of basic living costs.

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCMohammed Ramadan was clutching the Kalashnikov he had previously been assigned when we met him and several others in Damascus more than two weeks after the fall of the regime, at a “reconciliation center” run by HTS.

At the center, former military, police and intelligence officers, as well as anyone who was part of pro-Assad militia groups, can register for a temporary civilian ID card and surrender their weapons.

HTS announced a general amnesty for those who worked for the former regime.

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCWaleed Abdrabuh, a member of the group that looks after reconciliation centers in Damascus, said: “The aim is to return weapons issued by the former regime to the state. And for members of the force to be given a civilian identity card so they can be reintegrated into society.”

Under Assad, military conscription was compulsory for adult men. Recruits had to surrender their civilian IDs and were given military IDs instead.

Without a civilian ID card, it would be difficult for them to find work or move freely within the country, which partly explains why tens of thousands have turned up at centers in various cities.

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCAt the center in Damascus, a former office of Assad's Baath party, hundreds of men crowded the gate, eager to be let inside.

Many of them wanted to distance themselves from the crimes of the regime.

“I have not participated in any of their bad deeds. I consider them despicable actions. I did everything to avoid being part of massacres and crimes against Syrians,” said Mohammed al-Nadaf.

“I even tried to leave the military twice because I knew I was on the wrong side. But it was not possible to escape. The military had all my civil documents.”

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCSomar al-Hamoui, who served in the army for 24 years, said: “Most people don't know anything, do they? As for me, I don't know what happened in Saidnaya or any of the prisons. “

The BBC cannot independently verify their claims.

Anger at the regime and Assad's decision to flee to Russia on December 7, as the rebels closed in on Damascus, was also palpable.

“He (Bashar al-Assad) took a lot of money and ran away. He left all these people, all of us soldiers, to our own fate,” Somar said.

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCThere were many anxious faces in the crowds at the reconciliation center, but the mood seemed relatively amicable despite a 13-year civil war that has left more than half a million dead.

“Everyone told me it was safe to go and settle downtown. The safety guarantee made by HTS made a big difference,” said Mohammed al-Nadaf.

But reports of alleged revenge attacks involving killings, kidnappings and arson are increasingly coming from various parts of Syria. There are no reliable statistics confirming how many attacks have taken place, but dozens have been reported on social media.

Three judges ruling on property issues in the previously regime-held town of Masyaf in northwest Syria were killed last week – Munzer Hassan, Mohammed Mahmoud and Youssef Ghannoum. Sources at the hospital where their bodies were examined told the BBC that they had been hit in the head with a sharp object.

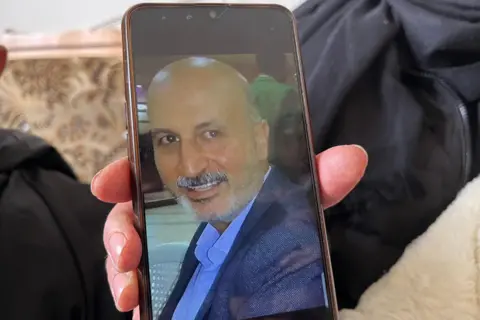

We went to the village of Alamerea to visit Munzer Hasan's home. It was bare, cold, and looked like it needed repair.

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBCMunzer's wife, Nadine Abdullah, told us she believes her husband was targeted because he is an Alawite, the minority sect from which the Assad family is descended and to which many of the former regime's political and military elite belong.

“Since they were civil and not criminal judges, I think they were killed simply because they were Alawites. All Alawites did not benefit from Bashar al-Assad. Those who worked for the regime were forced to follow orders, otherwise the brutal measures would be imposed on them,” Nadine said.

Munzer's brother Nazir said: “This is a crime against an innocent person. It is unacceptable. Those killed had nothing to do with the regime's politics. They were just working to support their poor families.”

Munzer was the father of four young children and was the only worker in his family, while also caring for his ailing father and brother.

His family said they are speaking out because they want similar deaths to be prevented in the future.

Aamir Peerzada/BBC

Aamir Peerzada/BBC“Everyone says that HTS did not commit the crime. But as the governing body now, they have to find out who did it. They must provide protection for all of us,” said Nadine.

The HTS interim government condemned the killing of the judges and said it would find the perpetrators. He also denied involvement in reprisal killings.

There have been protests in Masiaf since the killing of the judges, and many Alawites have told the BBC they now fear for their safety.

Although HTS announced an amnesty for Assad's forces, they also said those involved in torture and killings would be held accountable. It will be difficult to find a balance.

A few weeks after the fall of the regime, this is a delicate moment for Syria.

Additional reporting by Aamir Peerzada and Sanjay Ganguly.