The BBC

The BBCDawn breaks on Darwin Harbor and government ranger Kelly Ewin – whose job it is to catch and remove crocodiles – balances precariously on a floating trap.

Heavy rain clouds from the recently passed storm are overhead. The boat's engine has been cut, so it's almost silent now – except for the occasional splash coming from inside the trap.

“You have almost zero chance with these guys,” Ewin says as he tries to wrap a noose around the agitated reptile's jaw.

We are in Australia's Northern Territory (NT), home to around 100,000 wild saltwater crocodiles, more than anywhere else in the world.

The capital Darwin is a small coastal city surrounded by beaches and wetlands.

And as you quickly learn here in the NT, where there's water, there's usually crocodiles.

Saltwater crocodiles – or salties as they are known locally – were nearly driven to extinction 50 years ago.

After World War II, the uncontrolled trade in their furs skyrocketed and their numbers dropped to about 3,000.

But when hunting was banned in 1971, the population began to grow again – and quickly.

They are still a protected species, but no longer endangered.

The saltwater crocodile's recovery has been so dramatic that Australia now faces a different dilemma: managing their numbers to protect people and society.

“The worst thing that can happen is when people turn (against crocodiles),” explains crocodile expert Prof. Graham Webb.

“And then a politician will invariably come out with some kind of knee-jerk reaction (that) they're going to 'solve' the crocodile problem.”

Life with predators

The NT's hot temperatures and abundant coastal environment create the perfect habitat for the cold-blooded crocodiles, who need warmth to keep their body temperature constant.

There are also large populations of salt marshes in North Queensland and Western Australia, as well as parts of Southeast Asia.

While most species of crocodile are harmless, the saltie is territorial and aggressive.

Fatal accidents are rare in Australia, but they do happen.

A 12-year-old child was taken last year – the first crocodile death in the North North since 2018.

It's the busiest time of year for Ewin and his colleagues.

Breeding season has just begun, which means salties are on the move.

His team is out on the water several times a week checking the 24 crocodile traps around the city of Darwin.

The area is popular for fishing as well as some brave swimmers.

Crocodiles that are removed from the harbor are most often killed because if they are released elsewhere, they are likely to return to the harbor.

“It's our job to try to protect people as much as we can,” says Ewin, who has been in his “dream job” for two years. He was a police officer before that.

“Obviously we're not going to catch every crocodile, but the more we take out of the port, the lower the risk of encountering crocodiles and humans.”

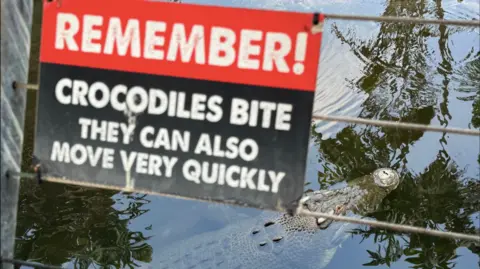

Another tool that helps keep society safe is education.

The NT Government is getting into schools with its 'Be Crocwise' program – which teaches people how to behave responsibly around crocodile habitats.

It was such a success that Florida and the Philippines are now looking to occupy it to better understand how the world's most dangerous predators can live alongside humans with minimal interactions.

“We live in crocodile country, so it's about how (we keep) safe around waterways – how do we respond?” says Natasha Hoffman, a ranger who runs the program in the NT.

“If you're on the boats when you're fishing, you have to be aware that they're there. They are ambush hunters, they sit, watch and wait. If there's an opportunity to get some food, that's what they'll do.”

In the NT, mass culling is currently off the table given the species' protected status.

However, last year the government approved a new 10-year crocodile management plan to help control the numbers, which increased the quota of crocodiles that can be killed annually from 300 to 1,200.

This is in addition to the work Ewin's team is doing to remove any crocodiles that pose a direct threat to humans.

Every time there is a death, it renews the debate about crocodiles living in close proximity to humans.

In the days after the 12-year-old girl was taken last year, then-territory leader Eva Lawler made it clear she would not allow the reptiles to outnumber the NT's human population.

Currently, it is 250,000, far exceeding the number of wild crocodiles.

This is a conversation that goes beyond the NT.

Queensland is home to about a quarter of the number of crocodiles in the Upper NT, but has many more tourists and more deaths, meaning talk of the cull sometimes features in election debates.

Big business

Apex predators may be controversial, but they are also a big drawcard for the NT – for tourists, but also for fashion brands who want to buy their skin.

Visitors can head to the Adelaide River to watch “crocodile jumping” – which involves feeding salties with bits of meat on the end of a stick if they can jump out of the water for the audience.

“I have to tell you to put on (the life jackets),” jokes Spectacular Jumping Croc Cruises head captain Alex “Wookie” Williams as he explains the boat's house rules.

“Something I shouldn't tell you… (is that) life jackets are pretty useless out here.”

For Williams, who has been obsessed with Crocs since he was a child, there are many opportunities to work alongside them.

“It's been booming for the last 10 years or so,” he says of the number of tourists coming to the region.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAgriculture, which was introduced when hunting was banned, also became an economic engine.

It is estimated that there are now around 150,000 crocodiles in captivity in the NT.

Fashion brands such as Louis Vuitton and Hermès, which sells a Birkin 35 crocodile bag for A$800,000 (£500,000; £398,000) – have all invested in the industry.

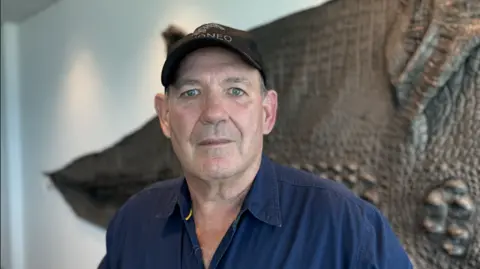

“The commercial incentives were effectively put in place to help people tolerate the crocodiles because we need a social license to be able to use the wildlife,” says Mick Burns, one of the NT's most prominent farmers who works with luxury brands.

His office is in downtown Darwin. A massive crocodile skin is spread across the floor. Nailed to the wall of the conference room is another skin that stretches at least four meters.

Burns is also involved in a ranch in remote Arnhem Land, about 500 km (310 mi) east of Darwin. There he worked with Aboriginal rangers to collect and hatch crocodile eggs to sell their skins to the luxury goods industry.

One of the area's traditional owners, Otto Bulmania Campion, who works alongside Burns, says more partnerships like theirs are critical to ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities share in the industry's financial benefits.

For tens of thousands of years, crocodiles have played an important role in local cultures, shaping their sacred histories, lives and livelihoods.

“My father, all the elders, used to go spearing crocodiles, take the skin and exchange it for tea, flour and sugar. (However) there was no money at that time,” says the Balngara man.

“Now we want to see our people handling reptiles.”

But not everyone agrees with farming as a practice — even if those involved say it helps with conservation.

The concern among animal activists lies in the way crocs are kept in captivity.

Although they are social animals, they are usually kept in separate pens to ensure their skins are immaculate – as a scrap between two territorial crocodiles is almost certain to damage a valuable commodity.

Aboriginal Swamp Ranger Aboriginal Corporation

Aboriginal Swamp Ranger Aboriginal CorporationEveryone in Darwin has a story about these awesome creatures, whether they want to see them hunted in greater numbers or more strictly conserved.

But the threat they continue to pose is not imaginary.

“If you go (swimming) in the Adelaide River to Darwin, there's a 100 per cent chance you'll get killed,” says Prof. Web unbiased.

“The only question is whether it will take five minutes or 10 minutes. I don't think you'll ever make it to 15 – you'll be ripped,' he adds, lifting his leg to reveal a huge scar on his calf – evidence of a close encounter with an angry female nearly forty years ago while collecting eggs.

He makes no apologies for what he calls the authorities' pragmatism to run the numbers and make crocodile money along the way – a way of life that, at least for the foreseeable future, is here to stay.

“We've done what very few people can do, which is take a very serious predator … and then manage them in such a way that society is willing to (tolerate) them.”

“You try to get people in Sydney, London or New York to put up with a serious predator – they won't.