BBC check

Ghetto images

Ghetto imagesUS President Donald Trump has imposed a 10% tariff for goods from most countries that have been imported into the United States with even higher percentages for what he calls the “oldest offenders.”

But how exactly were these tariffs developed – essentially import taxes? BBC Verify examines the calculations behind the numbers.

What were the calculations?

The White House

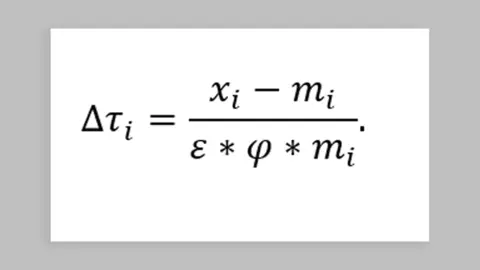

The White HouseBut the actual exercise was reduced to simple mathematics: take the trade deficit for the United States in goods with a particular country, divide that by the overall import of goods from that country and then divided this number into two.

A commercial deficit occurs when a country buys (import) more physical products from other countries than they are sold (export) to them.

For example, the United States is buying more goods than China than they are sold – there is a deficit of goods of $ 295 billion. The total amount of goods it buys from China is $ 440 billion.

Dividing 295 to 440 reaches you up to 67% and you divide it into two and round. Therefore, the tariff imposed on China is 34%.

Similarly, when applied to the EU, the White House formula has led to a 20%tariff.

Are Trump's tariffs “reciprocal”?

Many commentators have indicated that these tariffs are not reciprocal.

Reciprocal would mean that they are based on what the countries already charge the US in the form of existing tariffs, plus non -tariff barriers (things like regulations that increase costs).

However, the official document on the White House methodology makes it clear that they have not calculated this for all countries that have imposed tariffs.

Instead, the tariff rate is calculated on the basis that it will eliminate the deficit of goods in the United States with each country.

Trump broke away from the formula for imposing tariffs on countries that buy more goods from the United States than they sell to it.

For example, the United States is currently not managing a deficit of UK trade goods. Still, the United Kingdom is affected by a 10% tariff.

A total of more than 100 countries are covered by the new tariff regime.

“Much wider impacts”

Trump believes that the US is getting a bad world trade deal. According to him, other countries are flooding US markets with cheap goods – which hurts US companies and costs jobs. At the same time, these countries put barriers that make our products less competitive abroad.

So using tariffs to eliminate trade deficits, Trump hopes to revive US production and protect jobs.

Reuters

ReutersBut will this new tariff mode achieve the desired result?

BBC Verify has talked to a number of economists. The prevailing opinion is that although tariffs reduce the deficit of goods between the US and individual countries, they will not reduce the general deficit between the US and the rest of the world.

“Yes, this will reduce the bilateral trade deficit between the US and these countries. But obviously there will be much wider impacts that have not been caught in the calculation,” says Professor Jonathan Ports of King's College, London.

This is because the existing US general deficit is not solely guided by trade barriers, but how the US economy works.

On the one hand, Americans spend and invest more than they earn, and this difference means that the United States is buying more than the world than it is sold. So as long as this continues, the US can continue to maintain a deficit, despite the increase in rates with IT global trading partners.

Some commercial deficits may also exist for a number of legal reasons – not just to the tariffs. For example, buying food that is easier or more expensive to produce other countries.

Thomas Sampson of the London School of Economics said: “The formula has been processed to rationalize tariffs for charging countries with which the United States has commercial deficits. There is no economic justification for this and this will cost the world economy.”