BBC World Service

Ghetto images

Ghetto imagesPakistan has deported over 19,500 Afghans this month, among over 80,000 who have left the overtaking of the deadline since April 30, according to the UN.

Pakistan accelerated his desire to expel the homeless Afghans and those who had a temporary permission to stay, saying he could no longer cope.

Between 700 and 800 families are deported daily, said Taliban officials, with up to two million people expected to follow by the coming months.

Pakistani Foreign Minister Ishak Dar flew to Kabul on Saturday for talks with Taliban officials. His colleague Amir Khan Mutaki expressed “deep concern” about deportations.

Some Afghans at the border said they were born in Pakistan after their families escaped from conflict.

More than 3.5 million Afghans live in Pakistan, according to the UN Refugee Agency, including about 700,000 people who came after the UN's Taliban was taken up in 2021 estimated that half were not documented.

Pakistan has taken the Afghans in the decades of war, but the government says the large number of refugees now poses a risk to national security and is causing pressure on public services.

There is a recent jump in the border clashes between the security forces of both sides. Pakistan accuses them of fighters based in Afghanistan, which the Taliban deny.

The Pakistan Foreign Ministry said the two countries “discussed all the mutual interest issues” at a Saturday meeting in Kabul.

Pakistan extended the deadline for undocumented Afghans to leave the country until April 30.

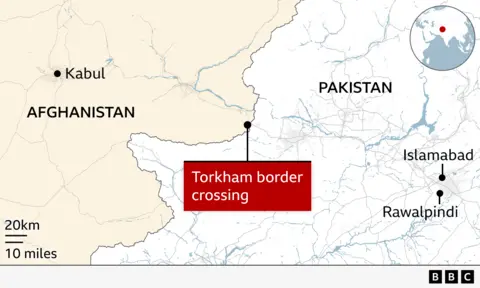

At the border point of Torkam, some expelled Afghans told the BBC that they had left Afghanistan decades ago – or never lived there.

“I have lived my whole life in Pakistan,” said Side Rahman, a second -generation refugee born and raised in Pakistan. “I got married there. What should I do now?”

Saleh, the father of three daughters, is worried about what life means under the Taliban rule to them. His daughters attend a school in Pakistan in the Punjab province, but in Afghanistan girls over the age of 12 are forbidden to do so.

“I want my children to study. I don't want their years to go to waste,” he said. “Everyone is entitled to education.”

Another man said to the BBC: “Our children have never seen Afghanistan and I don't even know what it looks like. It can take us a year or more to stay and find a job. We feel helpless.”

At the border, men and women pass through separate gates, under the clock of the armed Pakistan and Afghan security. Some of the return were adults – one man was transferred to a stretcher, another in a bed.

Military trucks sauce families from the border to temporary shelters. Those who initially stay there for several days from distant provinces, waiting for transport to their home regions.

Families accumulated under the sails to escape from the heat of 30C degrees as the rotating powder caught in the eyes and mouth. Resources are stretched and fierce arguments often explode from access to shelter.

Get between 4,000 and 10,000 Afghans (41 to 104 British pounds) from Kabul's organ, according to Heylayatulding to Hedyatllah Shinwari, a member of the Committee Committee, which has abandoned the camp.

Mass deportation has exerted significant pressure on the fragile infrastructure in Afghanistan, with an economy in a crisis and population, near 45 million people.

“We have solved most of the problems, but arriving people in such a large number naturally brings difficulties,” said Bakht Jamal Goshar, head of the Taliban of refugee affairs at the intersection. “These people left decades ago and left all their belongings behind them. Some of their homes were destroyed in 20 years of war.”

Almost every family told the BBC that Pakistani border guards limit what they can bring – a complaint sounded by some human rights groups.

Chardi said in response that Pakistan “has no policy that prevents Afghan refugees from taking their household items with themselves.”

A man sitting on the path of the bladder sun said his children asked to stay in Pakistan, the country where they were born. They were given a temporary residence, but it expired in March.

“We will never go back now. Not then how we were treated,” he said.

Additional reporting by Daniel Wittenberg and Malory Moinech