Getty Images

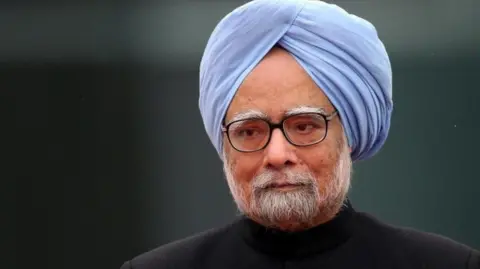

Getty ImagesFormer Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has died at the age of 92.

Singh was one of India's longest-serving prime ministers and was considered the architect of key liberalizing economic reforms, serving as prime minister from 2004-2014. and before that as Minister of Finance.

He was admitted to a hospital in the capital Delhi after his health deteriorated, reports said.

Among those who paid tribute to Singh on Thursday was Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who wrote on social media that “India mourns the loss of one of its greatest leaders.”

Modi said Singh's “wisdom and humility were always visible” during their interactions, and that he had “made tremendous efforts to improve people's lives” during his time as prime minister.

Priyanka Gandhi, daughter of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and a member of the Congress party, said Singh was “truly egalitarian, wise, strong-willed and courageous to the end”.

Her brother Rahul, who leads the Congress, said he had “lost a mentor and a leader”.

Singh was the first Indian leader since Jawaharlal Nehru to be re-elected after serving a full first term, and the first Sikh to hold the country's highest office. He made a public apology in Parliament for the 1984 riots in which around 3,000 Sikhs were killed.

But his second term was marred by a series of corruption allegations that dogged his administration. Many say the scandals were partly responsible for his party's crushing defeat in the Congress in the 2014 general elections.

Singh was born on 26 September 1932. in a desolate village in undivided India's Punjab province, lacking both water and electricity.

After attending Panjab University, he took an MA at Cambridge University and then a PhD at Oxford.

While studying at Cambridge, Singh's lack of funds bothered him, his daughter Daman Singh wrote in a book about her parents.

Getty Images

Getty Images“His tuition and living expenses amounted to about £600 a year. The Panjab University scholarship gave him about £160. For the rest he had to depend on his father. Manmohan was careful to live very meagerly. Subsidized dining room meals were relatively cheap at two shillings and sixpence.”

Daman Singh remembers his father as “completely helpless in the house and could neither boil an egg nor turn on the TV”.

Consensus builder

Singh rose to political prominence as India's finance minister in 1991, taking over as the country was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

His unexpected appointment ended a long and distinguished career as an academic and civil servant – he was an economic adviser to the government and became governor of India's central bank.

In his first speech as finance minister, he famously quoted Victor Hugo, saying that “no power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come”.

This served as the launching pad for an ambitious and unprecedented program of economic reform: he cut taxes, devalued the rupee, privatized state-owned companies and encouraged foreign investment.

The economy revived, industry revived, inflation was arrested, and growth rates remained consistently high throughout the 1990s.

Getty Images

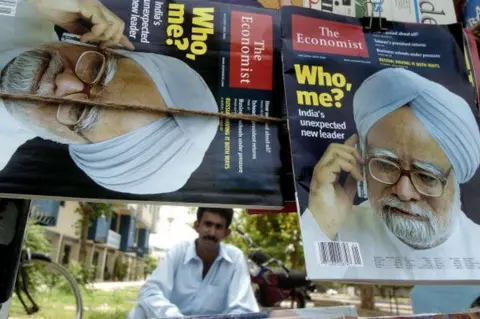

Getty Images“Accidental Prime Minister”

Manmohan Singh was a man who was acutely aware of his lack of a political base. “It's good to be a statesman, but to be a statesman in a democracy you must first win an election,” he once said.

When he tried to win the elections to India's lower house in 1999, he was defeated. Instead, he sat in the upper house, elected by his own party to Congress.

The same happened in 2004, when Singh was first appointed prime minister after Congress president Sonia Gandhi turned down the post – apparently to protect the party from damaging attacks on her Italian background. However, critics argued that Sonia Gandhi was the real source of power while he was prime minister, and that he was never truly in charge.

AFP

AFPThe biggest triumph of his first five-year term was bringing India out of nuclear isolation by signing a landmark deal providing access to US nuclear technology.

But the deal came at a price – the government's communist allies withdrew their support after protesting it, and the Congress had to make up for the lost numbers by attracting the support of another party amid allegations of vote-buying.

A consensus builder, Singh presided over a coalition of sometimes difficult, assertive and potentially recalcitrant regional coalition allies and supporters.

Although he earned respect for his integrity and intelligence, he also had a reputation for being soft-spoken and indecisive. Some critics argued that the pace of reform had slowed and he had failed to achieve the same momentum he had when he was finance minister.

AFP

AFPWhen Singh steered the Congress to a second, decisive electoral victory in 2009, he promised that the party would “rise to the top”.

But the luster soon began to wear off, and his second term was in the news mostly for all the wrong reasons: several scandals involving his cabinet ministers that allegedly cost the country billions of dollars, a parliament blocked by the opposition, and enormous political paralysis which led to a serious economic decline.

LK Advani, a senior leader in the rival BJP party, called Singh “India's weakest prime minister”.

Manmohan Singh defended his record, saying his government had worked with “the utmost commitment and dedication for the country and the welfare of its people”.

Pragmatic foreign policy

Singh adopted the pragmatic foreign policy followed by his two predecessors.

He continued the peace process with Pakistan – although that process was hampered by attacks blamed on Pakistani militants, culminating in the November 2008 gun and bomb attack in Mumbai.

He tried to end the border dispute with China by brokering a deal to reopen Tibet's Nathu La Pass, which had been closed for more than 40 years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSingh increased financial support for Afghanistan and became the first Indian leader to visit the country in nearly 30 years.

He also angered many opposition politicians by appearing to cut ties with India's old ally Iran.

A low profile leader

A studious former academic and bureaucrat, he was known to be reclusive and always kept a low profile. His social media account was mostly known for boring posts and had a limited number of followers.

A man of few words, his calm demeanor nevertheless won him many admirers.

Responding to questions about a coal scandal involving the illegal allocation of licenses worth billions of dollars, he defended his silence on the matter, saying it was “better than a thousand answers”.

AFP

AFPIn 2015 he was summoned to appear in court to answer to allegations of criminal conspiracy, breach of trust and corruption-related offences. An upset Singh told reporters that he was “open to legal scrutiny” and that “the truth will prevail”.

After his time as prime minister, Singh remained deeply involved in the issues of the day as a senior leader of the main opposition Congress party despite his advanced age.

In August 2020 he told the BBC in a rare interview that India must take three steps “immediately” to stem the economic damage from the coronavirus pandemic, which has sent the country's economy into recession.

The government should have provided direct cash assistance to the people, provided capital for businesses and fixed the financial sector, he said.

History will remember Singh for bringing India out of economic and nuclear isolation, although some historians suggest he should have retired earlier.

“I honestly believe that history will be kinder to me than the modern media, or for that matter the opposition parties in parliament,” he told an interviewer in 2014.

Singh is survived by his wife and three daughters.