BBC / Michael Steininger

BBC / Michael SteiningerAs the new Syria struggles to take shape, old threats are re-emerging.

The chaos after the overthrow of Bashar Assad “paves the way” for the so-called called Islamic State (IS) to return, according to a top Kurdish commander who helped defeat the jihadist group in Syria in 2019. He says the comeback has already begun.

“The activity of Daesh (IS) has increased significantly and the danger of resurgence has doubled,” according to General Mazloum Abdi, commander of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a mainly Kurdish militia alliance. “They now have more options and more opportunities.”

He says IS fighters have captured some weapons and ammunition left behind by Syrian regime troops, according to intelligence reports.

And he warns that there is a “real threat” that the militants will try to infiltrate SDF-run prisons here in north-east Syria, where around 10,000 of their men are being held. The SDF is also holding around 50,000 of their family members in camps.

Our conversation with the general was late at night, at a place we cannot disclose.

He welcomed the fall of the Assad regime, which had detained him four times. But he looked tired and admitted he was frustrated at the prospect of fighting old battles again.

“We fought against them (IS) and we paid 12,000 people,” he said, referring to SDF losses. I think on some level we're going to have to go back to where we were before.

The risk of an IS resurgence is heightened, he says, as the SDF comes under increasing attacks from neighboring Turkey – and rebel factions it supports – and must divert some fighters to that fight. He tells us that the SDF has had to halt counter-terrorist operations against IS and hundreds of prison guards – thousands strong – have returned home to defend their villages.

Ankara views the SDF as an extension of the PKK, outlawed Kurdish separatists who have waged a decades-long insurgency and are classified as terrorists by the US and EU. It has long wanted a 30-kilometer “buffer zone” in the Kurdish region of northeastern Syria. Since the fall of Assad, she has increasingly insisted on getting it.

“The number one threat now is Turkey because its airstrikes are killing our forces,” General Abdi said. “These attacks must stop because they distract us from focusing on the security of the detention centers, although we will always do our best,” he said.

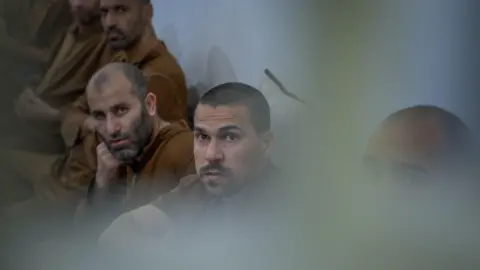

At Al-Sina, the largest prison for IS detainees, we saw the security levels and felt the tension among the staff.

The former educational institute in the city of al-Hasakah holds about 5,000 men – suspected IS fighters or supporters.

BBC / Michael Steininger

BBC / Michael SteiningerThe door of each cell is padlocked and locked with three bolts. The corridors are divided into sections by heavy iron gates. The guards are masked, with batons in their hands. Getting access here is rare.

We were allowed to peek inside two cells, but could not speak to the men inside. They were told we were journalists and given the opportunity to hide their faces. Few did. Most sat silently on blankets and thin mattresses. Two men were pacing the floor.

Kurdish security sources say most of the prisoners in Al-Sina were with IS until its last battle and were deeply committed to its ideology.

We were taken to meet a 28-year-old detainee – thin and soft-spoken – who did not want to be named. He said he spoke freely, but on the key issues he would not say much.

BBC / Michael Steininger

BBC / Michael SteiningerHe told us he left his native Australia at the age of 19 to visit his grandmother in Cyprus.

“From there one thing led to another,” he said, “and I ended up in Aleppo.” He claims he was working with an NGO in the city of Raqqa when IS took over.

I asked if he had blood on his hands and was he involved in killing anyone? “No, I wasn't,” he replied softly.

And did he support what IS is doing? “I do not wish to answer that question because it may have an effect on my case,” he replied.

He hopes to return to Australia one day, although he is not sure if he will be welcome.

There is also hope behind the wire at the Roj camp – about three hours away by car – that freedom is coming. Somehow.

This bleak space of tents – surrounded by walls, fences and watchtowers – is home to almost 3,000 women and children. They have never been tried or convicted, but are families of IS fighters and supporters.

There are a few British women in the camp. We met briefly with three of them. All said they were told by their lawyers not to talk.

In a wind-swept corner, we came across the woman we wanted to talk to – Saida Temirbulatova, 47, a former tax inspector from Dagestan. Her nine-year-old son, Ali, stood quietly by her side. She hopes that Assad's ouster will mean freedom for both of them.

BBC / Michael Steininger

BBC / Michael Steininger“The new leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (the head of the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) made a speech in which he said he would give freedom to everyone. We want freedom too. We want to leave, most likely to Russia. the only country that will take us.”

The camp manager tells us that others believe that IS will come to their rescue and crush them. She asked us not to use her name as she fears for her safety.

“After the fall of Assad, the camp is calm. Usually when it's this quiet it means women are organizing,” she said. “They have their bags packed ready to go. They say, “Soon we will come out of this camp and renew ourselves.” We will be back again as IS.

She says there is a visible change even in children who chant slogans and swear at passers-by. “They say, 'We'll come back and get you. It (IS) is coming soon.''

During our time at camp, many children raised the index finger of their right hand. This gesture is used by all Muslims in daily prayer, but is also widely used by IS fighters in propaganda images.

The women in Camp Roj are not the only ones packing.

Some Kurdish civilians in the town of al-Hasakah are doing the same – fearing a return of the jihadists and a new Turkish ground offensive in northeastern Syria.

Juan, 24, who teaches English, is getting ready to leave – reluctantly.

“I've packed my bag and I'm getting my ID and important documents ready,” he tells me. “I don't want to leave my home and my memories, but we all live in a state of constant fear. The Turks are threatening us and the doors are open to IS. They can attack their prisons. They can do whatever they want.”

Juan was already displaced once from the northwestern city of Aleppo at the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011. This time he wonders where to go.

“The situation requires urgent international intervention to protect civilians,” he says. I ask if he thinks he will come. “No,” he replies softly. But he asks me to mention his request.

Additional reporting by Michael Steininger and Matthew Goddard