BBC News

Family distribution

Family distributionIn January, Lina went to the police.

Her ex -partner threatened her at home in the Spanish seaside city of Benalmade. That day he seemed to raise his hand as if to hit her.

“There were violent episodes – she was scared,” recalls Lina Daniel's cousin.

When she reached the police station, she was interviewed and her case registered with Viogén, a digital instrument that evaluates the likelihood of a woman being attacked again by the same man.

Viogén – an algorithm -based system – asks 35 questions about abuse and its intensity, the access of the aggressor to weapons, his mental health and whether the woman has left or is considering leaving the relationship.

He then recorded the threat to her as “insignificant”, “low”, “environment”, “tall” or “extreme”.

The category is used to make decisions on the allocation of police resources to protect the woman.

Lina is considered a “average” risk.

She has requested a restrictive order in a specialized sex court for gender violence in Malaga so that her ex -partner cannot be in contact with her or share her residential space. The request was denied.

“Lina wanted to change the locks in her home so she could live with her children peacefully,” her cousin says.

Three weeks later she was dead. It is supposed that her partner used her key to enter her apartment and soon the house was set on fire.

While her children, mother and former partner escaped, Lina did not. Her 11-year-old son was widely reported to tell police that his father had killed his mother.

Lina's lifeless body was extracted from the charred interior of her home. Her ex-partner, the father of her three youngest children, was arrested.

Now her death raises questions about Viogén and his ability to keep women safe in Spain.

Viogén did not precisely predict the threat to Lina.

As a woman set at “average” risk, the protocol is that she will be followed again by a nominated police officer within 30 days.

But Lina was dead before. If it were a “high” risk, police tracking would have happened within a week. Could this have changed Lina?

Instruments to evaluate the threat of repetitive domestic violence are used in North America and throughout Europe. In the UK, some police forces use DARA (assessment of the risk of home abuse) – essentially a checklist. And dash (domestic abuse, lurking, harassment and evaluation of the violence based on honor) can be hired by the police or others as social workers to evaluate the risk of another attack.

But only in Spain is an algorithm, so tightly into police practice. Viogén was developed by the Spanish police and academics. It is used everywhere except the country of Basque and Catalonia (these regions have separate systems, although police cooperation is across the country).

The head of the Malaga National Police Family and the Women's Unit, CH INPS ISABEL ESPEJO, describes Viogén as “super important”.

“The work of every victim helps us very precisely,” she says.

Its officers deal with an average of 10 gender violence reports per day. And every month, Viogén classifies nine or 10 women as a “ultimate” risk of re -victimization.

The consequences of resources in these cases are huge: 24-hour police protection for a woman, until the circumstances change and the risk decreases. Women, rated as a “high” risk, can also get an employee.

A 2014 survey found that employees had accepted Viogén's assessment of the likelihood of multiple abuse 95% of the time. Critics suggest that police are terminating decisions about women's safety towards an algorithm.

CH Insp Espejo says that calculating the risk of the algorithm is usually adequate. But she admits – although Lina's case was not under her command – that something went wrong with Lina's assessment.

“I will not say that Viogene does not fail – it is.

But at “average” risk, Lina has never been a priority for the police. And does Lina's Viogene assessment had an impact on the court's decision to refuse her a restrictive order against her former partner?

The judicial authorities did not give us permission to meet with the judge, who refused Lina to dispose of her former partner, a woman attacked on social media after Lina's death.

Instead, another of Malaga's gender violence judges, Maria del Carmen Gutierrez, tells us in terms of general conditions that such an order needs two things: evidence of a crime and a threat of a serious danger to the victim.

“Viogén is one element that I use to assess this danger, but it is far from the only one,” she says.

Sometimes, the judge says, she makes restrictive orders in cases where Viogén has evaluated the woman as a “insignificant” or “low” risk. In other cases, she may conclude that there is no danger of a woman who is considered a “middle” or “high” risk of re -victimization.

Dr. Juan Jose Medina, a criminologist at the University of Seville, says that Spain has a “lottery lottery” for women applying to limit orders -some jurisdictions are much more likely to provide them than others. But we do not systematically know how Viogén affects the courts or police because the studies have not been done.

“How do police officers and other stakeholders use this instrument and how do they inform their decision making? We have no good answers,” he says.

The Spanish Interior Ministry often does not allow academics to have access to Viogén data. And there was no independent audit of the algorithm.

GEMMA GALDON, the founder of Eticas – an organization working on the social and ethical impact of technology – says that if you do not audit these systems, you will not know if they actually deliver police protection to the right women.

Examples of algorithmic bias are well documented elsewhere. In the US, the 2016 analysis of a recidivism instrument found that the black defendants were more likely than their white peers to be incorrectly evaluated as a higher risk of repeated violation. At the same time, the white defendants are more likely than the blacks' defendants to be misinterpreted as a low risk.

In 2018, the Interior Ministry of Spain did not give the green light to the ETICAS proposal to conduct a confidential, pro-Cano, internal audit. So instead, Gemma Galdon and her colleagues decided to convert engineer Viogén and perform an external audit.

They used interviews with women who have survived from domestic violence and publicly available information – including data from the judicial system for women who, like Lina, were killed.

They found that between 2003 and 2021, 71 women killed by their partners or former partners had previously reported domestic violence in the police. Those recorded in the Viogén system received risk levels of “minor” or “medium”.

“What we would like to know is that the percentages of errors that cannot be mitigated in any way? Or we could do something to improve how these systems put a risk and protect these women better?” He asks Gemma Galdon.

The head of gender violence research at Spain's Ministry of Interior Juan Jose Lopez-Osorio is rejecting Eticas's investigation: this was not done with VIogén data. “If you do not have access to the data, how can you interpret it?” He says.

And he protects against external audit, fearing that this can compromise both the security of women whose cases are recorded and virogenous procedures.

“What we know is that after a woman reports a man and is protected by the police, the likelihood of more violent violence is significantly reduced -we have no doubt about it,” says Lopez -Osorio.

Viogén has been developing since it was introduced to Spain. The questionnaire is refined and the category of the “insignificant” risk category will soon be removed. And even critics agree that it makes sense to have a standardized gender violence system.

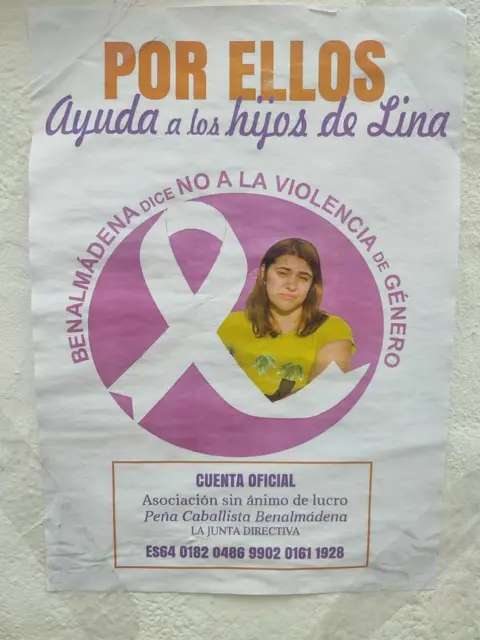

In Benalmadede, Lina's home became a sanctuary.

Flowers, candles and pictures of saints were left on the step. A small poster stuck on the wall announced: Benalmadea says no about gender violence. The community raised funds for Lina's children.

Her cousin, Daniel, says everyone is still trying to make the news of their death.

“The family that is destroyed – especially Lina's mother,” he says.

“She is 82 years old. I don't think there is anything more sad than that your daughter is killed by an aggressor in a way that could be avoided. Children are still in shock – they will need a lot of psychological help.”