PA Media

PA MediaQueen Elizabeth II was not officially informed for nearly a decade that one of her most senior courtiers had confessed to being a Soviet spy, according to recently released MI5 files.

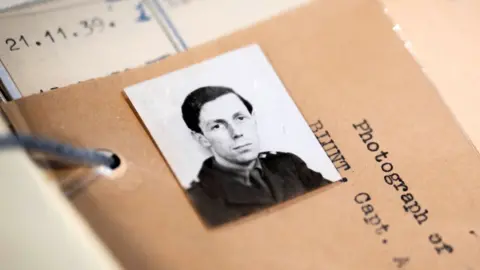

Art historian Anthony Blunt was for decades a surveyor of Queen's Pictures, overseeing the official Royal Art Collection, and in 1964. admits to having been a Soviet agent since the 1930s.

Documents released by MI5 show that although Blunt admitted to them that he had spied for the Russians during the Second World War, the late Queen herself was not officially told for almost nine years.

When she was briefed on the whole story in the 1970s, she was typically unfazed, taking it all “very calmly and without surprise,” according to declassified files provided to the National Archives.

PA Media

PA MediaThe decision to formally inform the Queen came amid growing fears in Whitehall that the truth would inevitably come out after Blunt, who was seriously ill with cancer, died. Journalists were now investigating the story and were no longer constrained by concerns of libel.

Suspicion first fell on Blunt in 1951 when fellow spies Guy Burgess and Donald McLean defected to the Soviet Union.

He was a close friend of Burgess's from their time at Cambridge together in the 1930s – part of the so-called Cambridge Five spy group.

During World War II, Blunt worked for MI5, after 1951. he was interviewed 11 times by the Security Service but always denied espionage.

Then American Michael Strait told the FBI that he had been recruited by Blunt himself as a Russian agent.

Getty Images

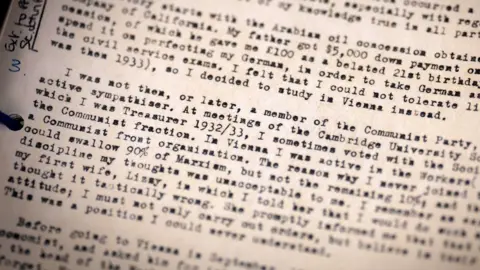

Getty ImagesIn April 1964 MI5 investigator Arthur Martin confronted Blunt and promised him immunity from prosecution.

His full confessions are included for the first time in these files. In addition to admitting his work during the war, he admitted that he had been in contact with the Russian intelligence service after the war.

Blunt said he met a Russian man named Peter before Burgess and McLean left, but he couldn't remember exactly why. He said the so-called Peter encouraged him to run away, but he refused.

The interrogator said Blunt was “not calm” as he spoke and each question “was followed by a long pause” as he “appeared to be debating with himself how to answer.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite Blunt's prominent position, few outside MI5 were informed of this confession. The Home Secretary and his most senior civil servant have been informed.

The Queen's private secretary was told only that Blunt was involved and that MI5 intended to question him.

It was agreed that if Blunt became seriously ill, she would be officially informed, as this could lead to the press covering his past.

PA Media

PA MediaIn March 1973, another memo file records that the Queen's private secretary spoke to her about the Blunt case. It reads: “She took it all very calmly and without surprise: she remembered that he had been a suspect since the end of the Burgess/McLean affair.”

Miranda Carter, Blunt's biographer, said her “hunch” was that Elizabeth II was told off the record some time after 1965.

She believes officials “wanted to maintain a veil of plausible deniability.” That the monarch took the news “calmly and without surprise” suggests to Carter that she must have known.

Blunt's past was finally revealed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in a statement to the House of Commons in 1979. He died in 1983. aged 75 after being stripped of his knighthood.

Other documents released by MI5 reveal:

- Cambridge spy Kim Philby says he would do it again after finally admitting he was a Russian agent for years

- Blunt feared his KGB chief would turn violent when he refused to join fellow spies Burgess and McLean and flee to Russia

- Film star Dirk Bogard has been warned by MI5 that he could be the target of a gay 'luring' attempt by the KGB

- MI5's chief investigator was baffled by Philby, admitting he could not determine whether he was a Soviet spy

PA Media

PA MediaUnlike civil services, MI5 is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act. He releases his archives as he chooses and some files are partially redacted.

Some of the documents published today will be included in an upcoming exhibition at the National Archives.

MI5 Director General Sir Ken McCallum said: “While much of our work must remain secret, this exhibition reflects our ongoing commitment to be open wherever we can.”