BBC Hindi

The BBC

The BBCVegetable seller Shivnarayan Dasana has never seen so many policemen descend on his village in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.

The 60-year-old lives in Tarapur in the industrial town of Pitampur, known for its automobile and pharmaceutical factories. The city has been tense since containers containing 337 tonnes of toxic waste from the site of one of the world's biggest industrial accidents arrived for disposal three weeks ago.

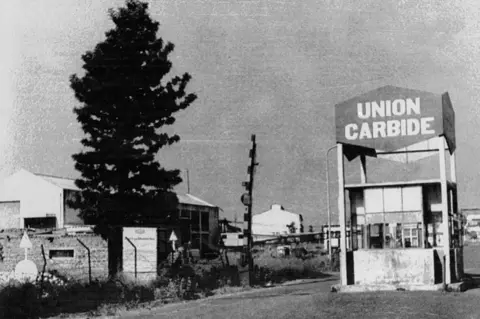

The waste transported from the now-defunct Union Carbide factory in the city of Bhopal – the site of the 1984 gas tragedy. killed thousands – caused fears among local residents.

They worry that dumping it near their homes could be harmful and even cause an environmental disaster.

Protests erupted on January 3, a day after the waste arrived in the city, escalating into stone-throwing and self-immolation attempts.

Since then, heavy police patrols near the waste facility have transformed Tarapur and surrounding areas in a virtual garrison.

Police have registered seven cases against 100 people since the protests began, but city residents continue to express concern about industrial pollution at smaller public gatherings.

The toxic waste cleared from the Bhopal factory included five types of hazardous materials – including pesticide residues and “perpetual chemicals” left over from the manufacturing process. These chemicals are so named because they retain their toxic properties indefinitely.

Over the decades, these chemicals have seeped into the environment, posing a health hazard to people living around the Bhopal factory.

But officials dismiss concerns that dumping is causing environmental problems in Pitampur.

Senior official Swatantra Kumar Singh outlined the phased process in an attempt to reassure the public.

“Hazardous waste will be incinerated at 1200C (2192F), with test batches of 90kg (194.4lb) followed by 270kg batches over three months if toxicity levels are safe,” he said.

Mr Singh explained that “four-layer filtration will purify the smoke”, which will prevent toxins from entering the air, and combustion residues will be “sealed in a double-layer membrane” and “buried in a specialized landfill” to prevent soil and groundwater pollution.

“We have trained 100 'master trainers' and are holding sessions to explain the disposal process and build public confidence,” said administrator Priyank Mishra.

Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Mohan Yadav also defended the dumping, calling it safe and necessary. He urged residents to raise their concerns legally, noting that the dumping was done only after a Supreme Court order.

However, environmental experts have different opinions about the process.

Some like Subhash C Pandey believe that dumping poses no risk if done properly. Others, like Shyamala Mani, call for alternatives to incineration. She claims that burning increases residual slag and releases harmful toxins such as mercury and dioxins.

Ms Mani suggests that bioremediation, a process that uses microorganisms to break down harmful substances in waste, could be a more efficient and environmentally friendly solution.

But residents remain skeptical.

“This is not just waste. It is poison,” said Gayatri Tiwari, a mother of five in Tarapur village. “What's the point of life if we can't breathe clean air or drink clean water?”

Pollution is an undeniable reality for the residents of Pithampur. Residents cite past groundwater contamination and ongoing health problems as reasons for skepticism.

The city's rapid industrial growth in the 1980s led to an accumulation of hazardous waste, contaminating water and soil with mercury, arsenic and sulfates. Until 2017 the federal agency Central Bureau of Pollution Control noted serious pollution in the area.

Locals claim that many companies do not comply with rules for disposing of non-hazardous waste, choosing to dump it into soil or water. The tests in 2024. showed increased harmful substances in the water. Activists have linked this to alleged environmental violations at the waste facility, but authorities have denied this.

“The water filters in our homes don't last two months. Skin diseases and kidney stones are now common. The pollution has made life unbearable,” said Pankaj Patel, 32, of Chirakhan village, pointing to his water purifier, which has to be replaced frequently.

Srinivas Dwivedi, regional officer of the State Pollution Control Board, dismissed the concerns, saying it was “unrealistic” to expect pre-industrial conditions in Pithampur.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMeanwhile, in Bhopal, nearly 230 kilometers (143 miles) from Pitampur, activists say the dumping process is distracting from much bigger problems.

After the disaster, the toxic material sat in the canned factory for decades, contaminating groundwater in surrounding areas.

More than 1.1 million tons of contaminated soil remains at the Union Carbide plant, according to a 2010 report. of the National Institute for Environmental Engineering and the National Institute for Geophysical Research.

“The government is making a show of dumping 337 metric tonnes while ignoring the much bigger problem in Bhopal,” said Nityanand Jayaraman, a leading environmentalist.

“Pollution has worsened over the years but the government has not done much to tackle it,” added Rachna Dhingra, another activist.

Government estimates put 3,500 people dead shortly after the gas leak, with more than 15,000 dying later. Activists claim the death toll is much higher, with victims still suffering from the side effects of the poisoning.

“Given Pithampur's history of pollution, residents' fears are well-founded,” Mr. Jayaraman said.

Officials said they were “only dealing with waste as per the court's directive”.

But the reality in Bhopal has deepened mistrust among the people of Pitampur, who are now ready to take to the streets again to oppose the dumping.

Vegetable supplier Shivnarayan Dasana said the problem goes beyond the waste itself.

“It's about survival – ours and our children's,” he said.

Follow BBC News India Instagram, youtube, Twitter and Facebook.