Getty Images

Getty ImagesDavid Lynch once said that he was inspired to become a filmmaker when, while painting, he inexplicably heard a gust of wind and saw the work moving across the canvas.

The moment defines his obsession with “seeing pictures move,” but also his flair for the strange – warping the realities of the small and big screen for nearly 40 years.

The 78-year-old American director, who has died months after being diagnosed with emphysema, has become the modern face of strange, disturbing worlds often hidden in society's everyday life – from the television series Twin Peaks to films such as Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire.

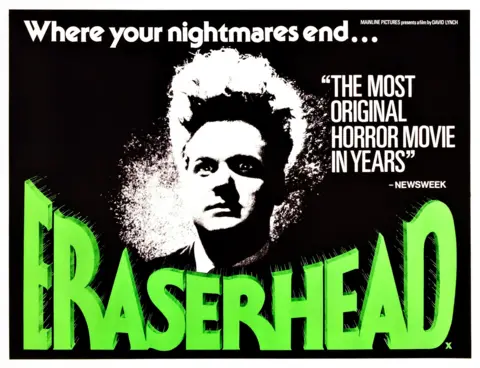

A self-proclaimed dreamer, Lynch burst onto the scene via the midnight movie circuit with 1977's Eraserhead. Disorienting horror, a commentary on male paranoia, sets the layered pattern that runs through his work.

Four decades later, he lived to see his style immortalized as an adjective in the Oxford Dictionary. Lynchian, readsblurs “surreal or macabre elements with the mundane,” an accolade fitting for the four-time Oscar nominee turned body of work whose character was as large as his films.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDavid Keith Lynch was born in Missoula, Montana on January 20, 1946. The son of a Department of Agriculture researcher, he spent much of his early life moving from state to state with his brother and sister.

However, Lynch's parents encouraged his artistic ambitions from an early age. Speaking to Rolling Stone in 1990, he said his mother “saved him” by encouraging him to draw on scrap paper instead of using coloring books where “the whole idea is to stay between the lines”.

This ethos inspired his films, tinged with a rebellious streak that he teased lasted from age 14 to 30. “People rebel so long these days,” he reasoned, “because we're built to live longer.”

A youthful disenchantment with the tranquility of suburban life left him yearning for “something unusual to happen” to challenge the superficiality of 1950s family ideals, a dark dream that his films and shows bring to life.

Lynch's black-and-white debut Eraserhead achieved this vision far more successfully than his art school years, with its central character descending into madness after fathering a terrifying baby.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCritics were left confused, but its late-night box-office success sparked a breakthrough when an audience member recommended it to Mel Brooks, who asked him to direct The Elephant Man.

Co-written by Lynch, the film's cast of future screen icons, including John Hurt as Merrick and Anthony Hopkins, transformed the story of stigma into an emotional, critical hit, surpassing the original stage play.

It saw Lynch receive Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Adapted Screenplay, as part of the film's eight nominations, including Best Picture.

But if Hollywood thought it had found a new master of blockbusters, Tinseltown quickly discovered that Lynch had no interest in going mainstream with his 1984 adaptation. of the science fiction epic Dune.

Featuring dubious special effects, costumes and rock star Sting slathered in baby oil, Charles Bramesco of the Guardian wrote that Lynch's experiments left the franchise “radioactive for decades.” “I'm proud of everything except Dune,” Lynch would later say in a YouTube Q&A, while admitting elsewhere that it nearly “killed” his career.

Coffee, cherry pie… and Twin Peaks

The wounds began to heal, however, when he returned to double down on his trademark style – putting his fascination with America's dirty underbelly into focus.

Blue Velvet, starring Dune's Kyle McLachlan, follows a small-town boy trapped in the underworld after discovering a severed ear. Part brutal and violent, it divided critics but earned Lynch his second Oscar nomination for best director.

“This is the way America is to me,” Lynch later described the film in his book, Lynch on Lynch. “There's a very innocent, naïve quality to life, and also horror and sickness.”

He won the prestigious Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival for the romance Wild at Heart in 1990. starring Nicolas Cage, Laura Dern and Willem Dafoe.

But it was Lynch's belief that American beauty and horror were two sides of the same coin, honed in his TV project Twin Peaks, released that year, that defined him.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn paper, the disturbing drama explores the dark events in an American logging town following the murder of beauty queen Laura Palmer, brought to life hauntingly by Sheryl Lee.

But viewers were truly captivated by what he offered on screen: a dreamlike nightmare of wonderfully idiosyncratic characters, including FBI agent Dale Cooper, once again played by Kyle MacLachlan, in the seeming comfort of a picket fenced America – including cherry pie and coffee – before a steadfast to reach into living rooms with the chilling undercurrent of sexual violence and murder. It was one that had no previous place on American television.

The ABC show won three Golden Globe Awards in 1991, including Best TV Drama Series and Best Actor in a TV Drama for MacLachlan.

“Without Twin Peaks and its great expansion of television, half of your favorite shows wouldn't exist.” writes James Parker for The Atlantic.

The show, he continued, “effectively renegotiated television's contract with its audience.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt didn't matter much that the second season flopped after the killer was revealed. TV was no longer safe, it was instinctively alive – ideas about the big screen and production values somehow came out in living rooms in an era when the screen still ruled.

In 1992 viewers were brought back to Twin Peaks with a feature film prequel, Fire Walk With Me, but nothing matched the original series.

When the nation asked “Who Killed Laura Palmer?”, it wasn't just about solving the mystery, it was about taking refuge from the rotten reality that society would rather ignore. Lynch had discovered his darkness.

He would eventually shift the focus back to the big screen to attack Hollywood's diabolical tricks of fame, glamour, deceit and loss of identity in films informally known as his Los Angeles Trilogy.

This began with 1997's Lost Highway, before 2001's Mulholland Drive. – perhaps the closest in terms of aesthetics to Twin Peaks.

The psychological drama received critical acclaim, earning Lynch his third Academy Award nomination for Best Director and winning Best Director at Cannes. In recent years, it has also been recognized for its queer themes, particularly between Naomi Watt and Laura Haring's characters, which challenged the traditional Hollywood storytelling of the time.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast came 2006's Inland Empire, Lynch's last feature film, which proved to be as mind-blowing as ever – showing Hollywood star culture without mercy.

As Mike Muncer told BBC Arts' Inside Cinema: “Lynch lures us in with the promise of familiar, traditional genre thrills and mysteries as a safety net before that weirdness starts to creep in.

“Eventually, the mystery box opens, revealing the darker, more sinister story that Lynch has actually been telling us all along.”

A cult icon

In his later years, Lynch enjoyed a revered cult status. In 2017 he directed Twin Peaks: The Return, a new series set 25 years after the events of the original series, with much the same cast.

Meanwhile, the series' legacy lives on, inspiring dramas like True Detective and the acclaimed 2023. playstation survival horror game Alan Wake II.

Away from the camera, Lynch admitted that he sometimes struggled to balance the “complicated business” of fatherhood with his career.

He welcomed four children — Jennifer, Austin, Riley and Lula — with ex-wives Peggy Reavey, Mary Fisk and Mary Sweeney and estranged wife Emily Stoffle.

“I love all my kids and we get along great, but in the early years, before you can bond with them, it's hard,” he told Vulture. “Work is the main thing, and I know that I have caused suffering because of it. But at the same time, I have a huge love for children.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough Lynch never returned to feature directing to give himself another shot at the elusive Oscar win, he did receive a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy in 2019. He also made a cameo appearance in Steven Spielberg's 2022 semi-autobiographical film, The Fablemans, playing director John Ford.

His artistic pursuits increasingly diversified towards the end of his life, from his initial passion for painting to music. Just last year he released Cellophane Memories, an album with Chrystabell. This is in addition to his previous work producing music videos for artists such as Moby and Nine Inch Nails.

Discussing his emphysema diagnosis last summer, he said he was in “great shape” and “will never retire.”

He added that the diagnosis was “the price he had to pay” for his smoking habit, although he did not regret the pleasure it gave him.

But his condition worsened after months. In an interview with People magazine in November, Lynch said she needed oxygen to walk.

Yet his ideas live on, as unique as the way he describes their perception.

Speaking to musician Patti Smith on BBC Newsnight in 2014, he said: “I get ideas in bits and pieces. It's like there's a puzzle in the other room – all the pieces fit together.

“But in my room they're just turning me piece by piece.”