The BBC

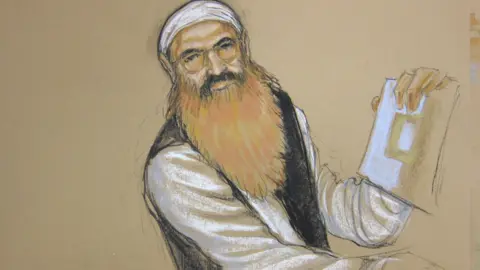

The BBCThe accused mastermind of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US will no longer plead guilty on Friday after the US government decided to block a plea deal reached last year.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, often referred to as KSM, was due to enter his pleas before a military court at the Guantanamo Bay naval base in southeastern Cuba, where he has been held in a military prison for nearly two decades.

Mohammed is the most famous prisoner at Guantanamo and one of the last detainees at the base.

But a federal appeals court on Thursday night halted proceedings scheduled to hear government requests to overturn plea deals for Muhammad and two co-defendants, which it said would cause “irreparable” harm to both him and the public.

A three-judge panel said the delay “should not be construed in any way as a decision on the merits” but was intended to give the court time to receive full briefing and hear arguments “on an expeditious basis”.

The delay means the matter will now fall to the incoming Trump administration.

What was supposed to happen this week?

In a hearing that began Friday morning, Muhammad was expected to plead guilty to his role in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, when hijackers seized passenger planes and crashed them into the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon outside Washington. Another plane crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers fought back.

Mohammed is charged with crimes including conspiracy and murder, with 2,976 victims listed in the indictment.

He previously said he planned “Operation 9/11 from A to Z” – hatching the idea of training pilots to fly commercial jets into buildings and passing those plans on to Osama bin Laden, leader of the militant Islamist group al-Qaeda , in the mid-1990s.

Friday's hearing was to be held in a courtroom on the base, where family members of the slain and the press would sit in a viewing gallery behind thick glass.

Why is all this happening 23 years after 9/11?

Preliminary hearings, held in a military court at the naval base, have dragged on for more than a decade, complicated by questions about whether the torture Mohammed and other defendants suffered while in U.S. custody tainted the evidence.

After his arrest in Pakistan in 2003 Muhammad spent three years in secret CIA prisons known as “black sites,” where he was subjected to simulated drowning or “waterboarding” 183 times, among other so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” that included sleep deprivation and forced nudity.

Karen Greenberg, author of The Least Worst Place: How Guantanamo Became the World's Most Notorious Prison, says the use of torture has made it “virtually impossible to bring these cases to trial in a way that respects the rule of law and American jurisprudence.” .

“It is obviously impossible to present evidence in these cases without the use of evidence obtained through torture. Furthermore, the fact that these individuals were tortured adds another level of complexity to the charge,” she says.

The case also ends up in military commissions, which operate under different rules than the traditional American criminal justice system and slow down the process.

The agreement was reached last summer after about two years of negotiations.

What does the agreement include?

Full details of the deals reached with Mohammed and two of his co-defendants have not been disclosed.

We know a deal means he won't face a trial with the death penalty.

At a court hearing on Wednesday, his legal team confirmed that he had agreed to plead guilty to all charges. Muhammad did not address the court in person, but engaged with his team as they reviewed the agreement, making minor adjustments and wording changes with the prosecution and the judge.

If the deals are confirmed and the pleas are accepted by the court, the next steps will be to appoint a military jury, known as a panel, to hear evidence during a sentencing hearing.

In court on Wednesday, it was described by lawyers as a form of public trial where survivors and family members of those killed would be given the opportunity to testify.

Under the settlement, the families will also be able to ask questions of Mohammed, who will have to “fully and truthfully answer their questions,” lawyers said.

Central to the prosecution's agreement to the deals was the assurance “that we could present whatever evidence we deemed necessary to establish historical evidence of the defendant's involvement in what happened on 9/11,” prosecutor Clayton G. Trivet Jr. , said in court Wednesday.

Even if the pleas proceed, it will be many months before these proceedings begin and ultimately a verdict is handed down.

Reuters

ReutersWhy is the US government trying to block applications?

US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin appointed a senior official who signed the deal. But he was traveling at the time he was signed and was reportedly surprised, according to the New York Times.

Days later, he tried to overturn it, saying in a memorandum: “The responsibility for such a decision must rest with me as a higher authority.”

However, both a military judge and a military appeals panel decided that the deal was valid and that Mr. Austin had acted too late.

In another attempt to block the deal, the government this week asked a federal appeals court to intervene.

A court filing said Muhammad and the other two men were accused of “committing the most outrageous criminal act on American soil in modern history” and that implementing the plea deals would “deprive the government and the American people of a public trial regarding the culpability of defendants and the possibility of the death penalty, despite the fact that the Secretary of Defense has legally withdrawn these agreements.”

After the deal was announced last summer, Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell, then the House leader, released a statement describing it as a “disgusting abdication of the government's responsibility to protect America and deliver justice.”

What did the families of the victims say?

Some families of those killed in the attacks also criticized the deal, saying it was too lenient or lacked transparency.

Speaking to the BBC's Today program last summer, Terry Strada, whose husband Tom was killed in the attacks, described the deal as “giving the Guantanamo Bay detainees what they want”.

Ms Strada, the national chairman of the 9/11 campaign group Families United, said: “It's a victory for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the other two, it's a victory for them.”

Other families see the settlements as a path to verdicts in the complex and lengthy proceedings and were disappointed by the government's latest intervention.

Stefan Gerhard, whose younger brother Ralf was killed in the attacks, had flown to Guantanamo Bay to watch Mohammed plead guilty.

“What is the ultimate goal of the Biden administration? So they get the stay and it drags on into the next administration. For what purpose? Think about families. Why are you prolonging this saga?” he said.

Mr Gerhardt told the BBC the deals were “not a victory” for the families but that it was “time to find a way to end this, to convict these men”.

Families on base were meeting the press when news of the delay was made public.

“This was supposed to be a time of healing. We'll get on that plane still with that deep feeling of pain – it's just never ending,” said one.

Why are the Guantánamo trials taking place?

Muhammad has been held in a military prison at Guantanamo Bay since 2006.

The prison was opened 23 years ago – on January 11, 2002. – during the “war on terror” that followed the 9/11 attacks, as a place to hold terror suspects and “illegal enemy combatants”.

Most of those held here have never been charged and the military prison has faced criticism from human rights groups and the United Nations for its treatment of detainees. Most of them have already been repatriated or resettled in other countries.

There are currently 15 in the prison, the lowest number at any point in its history. All but six of them have been charged with or convicted of war crimes.